The participation of Chinese-American in the armed forces and in industries brought new self-confidence and acceptance by the larger society. The repeal of the Exclusion Act, along with the War Brides Act and the Refugee Acts enabled women and families, mostly via Hong Kong, to settle in Chinatown.

The participation of Chinese-American in the armed forces and in industries brought new self-confidence and acceptance by the larger society. The repeal of the Exclusion Act, along with the War Brides Act and the Refugee Acts enabled women and families, mostly via Hong Kong, to settle in Chinatown.

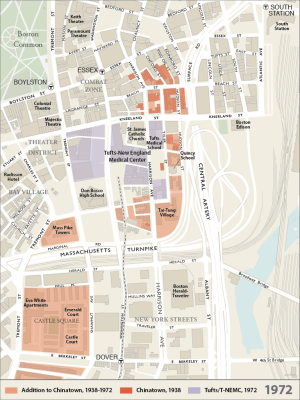

As the community grew, major development projects threatened the community – the expansion of Tufts-New England Medical Center, the Central Artery, and the Massachusetts Turnpike. On the other hand, Urban Renewal brought affordable housing and community facilities, which helped stabilize Chinatown as a viable community.

- Retail and Garment industry continue decline.

- Other ethnic neighborhoods diminish as families seek better housing.

- Urban Renewal for slum clearance.

- Highways seen as necessary for region and downtown.

- Laundries decline as restaurants expand in Chinatown and suburbs.

- Central Artery and Turnpike Extension built to revitalize downtown.

- First phase of Urban Renewal clears West End and New York Streets.

- South Cove Urban Renewal Plan stabilizes Chinatown/NE Medical Center expansion.

- Garment buildings become opportunities for re-use by Chinatown and Tufts NE Medical Center.

- Scollay Square adult entertainment relocates to lower Washington St.

- Gentrification of Bay Village.

- 1965 Immigration Act opens pent-up Chinese immigration.

- Chinese expand south of Kneeland St. and to South End

- One-step-up families move to Brighton/Allston.

- Professionals settle in the suburbs.

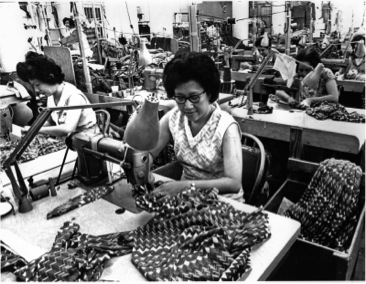

- Chinese women keep garment industry alive temporarily

- Syrians move to the South End, West Roxbury and beyond.

Population – 1970:

- Chinatown – 2900*

- Boston – 7,007

- Mass – 14,012

* ABCD Report – Chinese in Boston, 1970

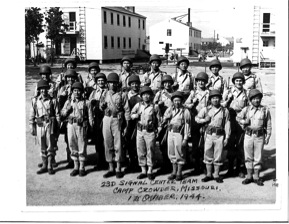

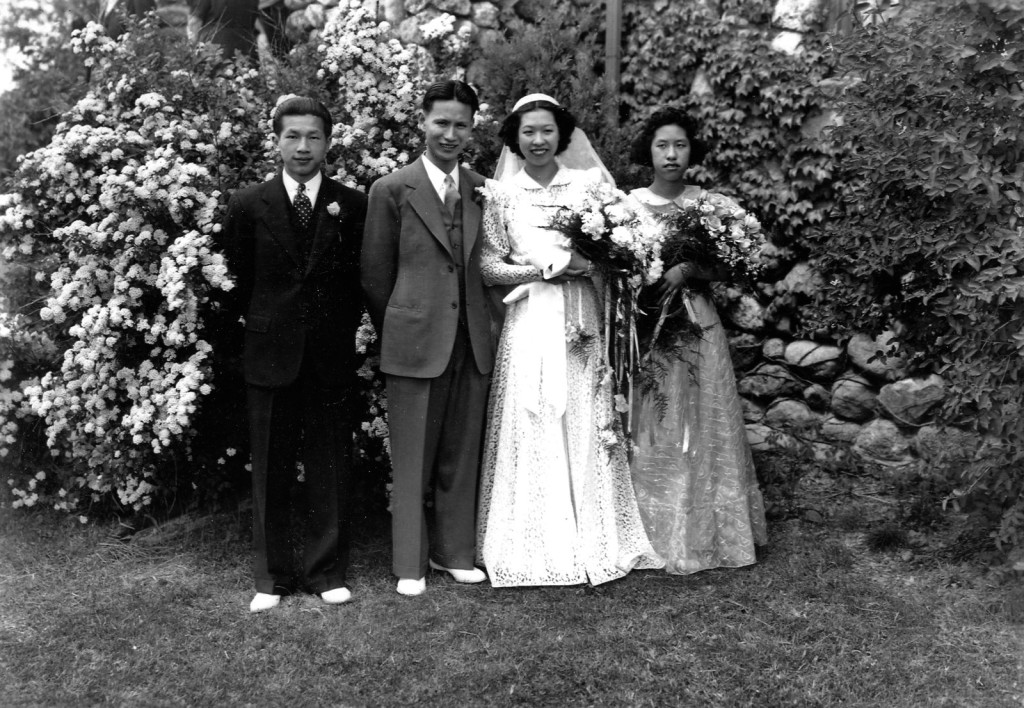

CHINESE IN WORLD WAR II

As WW II became a total global war, Chinese both volunteered and were drafted. Even though they were often organized into all-Chinese units, for the first time many of them lived and functioned as members of the larger society.

A chapter of the American Legion was organized. Working with the traditional organizations and using volunteer labor, they created a space for meeting and networking. With acceptance and confidence, the veterans engaged in the larger society, expanded businesses and became activists to meet the needs of the growing community.

At the same time, the women of Chinatown, as with women everywhere in the United States, went to work in defense factories and in offices, beyond the laundries, restaurants and grocery stores.

Two major events dramatically changed the future of Boston’s Chinatown – the participation of the Republic of China in WWII on the side of the Allies, and the establishment of the Peoples’ Republic of China in 1949. Each of these events resulted in changes in immigration laws, or the creation of new laws, which in turn brought large numbers of new Chinese immigrants to the United States, many of whom settled in Boston’s Chinatown.

With China as an essential ally, Congress finally repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. However, this was mostly a symbolic act because of the restrictive quota. Other laws were enacted at the conclusion of WWII, which had a greater impact on the growth of the population in Chinatown. One was the War Brides Act, which permitted returning GI’s to bring their foreign born wives to the United States. The acts were primarily for the European region but for the Chinese, it was the first legal way to start families.

With the victory of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, immigration from the Mainland was essentially stopped. The subsequent upheaval caused by the radical social changes (Land Reform, Great Leap Forward, etc.) created a huge influx of Chinese refugees to then British colony Hong Kong, and other Overseas Chinese communities in South-East Asia. With the U.S. locked in struggle with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the People’s Republic of China in the Cold War, the Refugee Acts were passed to enable displaced families to emigrate. Again, the main beneficiaries were Eastern Europeans but Chinese were also included. These WWII and the Cold War changes in immigration laws, helped not only to increase in the population in Boston’s Chinatown, it also help bring an end to the imbalance in Chinatown’s population mix characterized by the “Bachelor Society”.

Most of the new immigrants came from Hong Kong bringing new fashions, skills in garment manufacturing and Cantonese. At the Kwong Kow School, the language of instruction changed from Taishanese to Cantonese. Those Chinese women who were skilled and experienced enabled the declining garment industry to continue functioning for many more years until its inevitable demise in the face of overseas competition. At the same time, it provided jobs and income to the community.

Most settled in Chinatown which expanded south of Kneeland Street. The remaining Syrians left for the South End and the suburbs.

COMMUNITY ENDANGERED

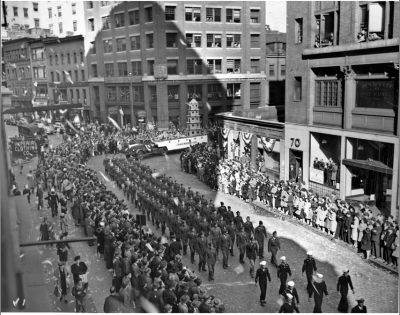

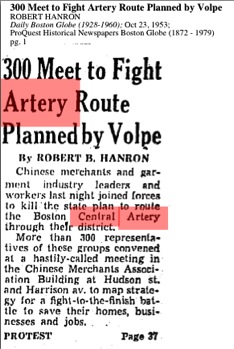

While Boston’s Chinatown’s population grew, its very existence was threatened by highway construction, urban renewal and other development projects in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. The Central Artery was built to alleviate traffic congestion in downtown Boston and there were alternatives that would have completely demolished most of Chinatown.

(8) Proposed highway route.

The On Leong Merchants Association in conjunction with the Garment Industry could not stop the highway but fought hard to minimize the damage. The original plan was to demolish the newly finished Merchants Association Building but a compromise was reached to retain part of the building.

he extension of the Massachusetts Turnpike into the downtown required the taking of land, by eminent domain, south and east edges of Chinatown. Hundreds of families were displaced destroying the Hudson St neighborhood, replacing the row of houses with a ramp and retaining wall.

URBAN RENEWAL

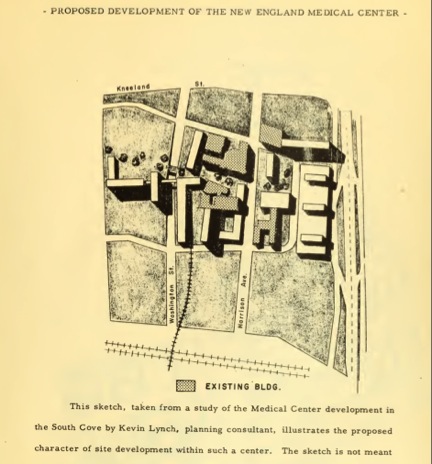

Early urban renewal projects like the West End project involved total clearance of substandard housing. Just south of Chinatown, the New York Streets neighborhood was totally cleared displacing hundreds of families. The old housing occupied by Chinatown was vulnerable to similar action. At the same time, Tufts New England Medical Center (TNEMC) was expanding and their Development Plan viewed the adjacent streets of Chinatown as potential sites.

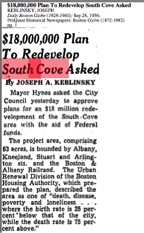

In 1956, the Urban Renewal Division of the Housing Authority described the South Cove area as one of “death, disease, poverty and loneliness…”, to justify a project to demolish 90% of the district including “the largest section of Chinatown’s residential district…”. “Possible re-uses of the area included expansion of the New England Medical Center, office and hotel building, merchandise mart, light manufacturing, housing and neighborhood facilities…”

In 1960 before that plan could be implemented, John Collins was elected Mayor in response to the outrage caused by the destruction of the West End under urban renewal and the damage from the Central Artery. He reorganized the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) to plan and coordinate all development projects. Collins and Ed Logue, head of the BRA had learned the lessons of previous approaches. Land takings were minimized and compensation for displaced residents was made fairer. Planning was more comprehensive and public participation was required.

Chinatown and its needs were addressed in planning for the development of South Cove– an area that included residential Chinatown, TNEMC, Bay Village and parts of the Theater District. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) coordinated the community to advocate for the interests of the community. The plan set boundaries to the expansion of the TNEMC, reorganized street patterns, and provided sites for affordable housing, a replacement for the Quincy School, and community facilities.

South Cove Urban Renewal Plan. Boston Redevelopment Authority, 1965